Archaeology at San Miguel del Vado

The village of San Miguel del Vado (sometimes spelled “Bado”) is located in northern New Mexico on the west bank of the Pecos River along Highway 3 south of Interstate 25 (Figure 1). It is the founding settlement of a Spanish community land grant made Governor Chacón in 1794 in response to an application by some 52 families. These families sought to settle the area around “El Vado,” a preferred river crossing located about 20 miles downstream from Pecos Pueblo. The governor granted the applicants more than 300,000 acres of land that included the river, river valley, and surrounding mesas, which were to be divided among and shared by the vecinos—a term used to describe the citizens of the land grant.

|

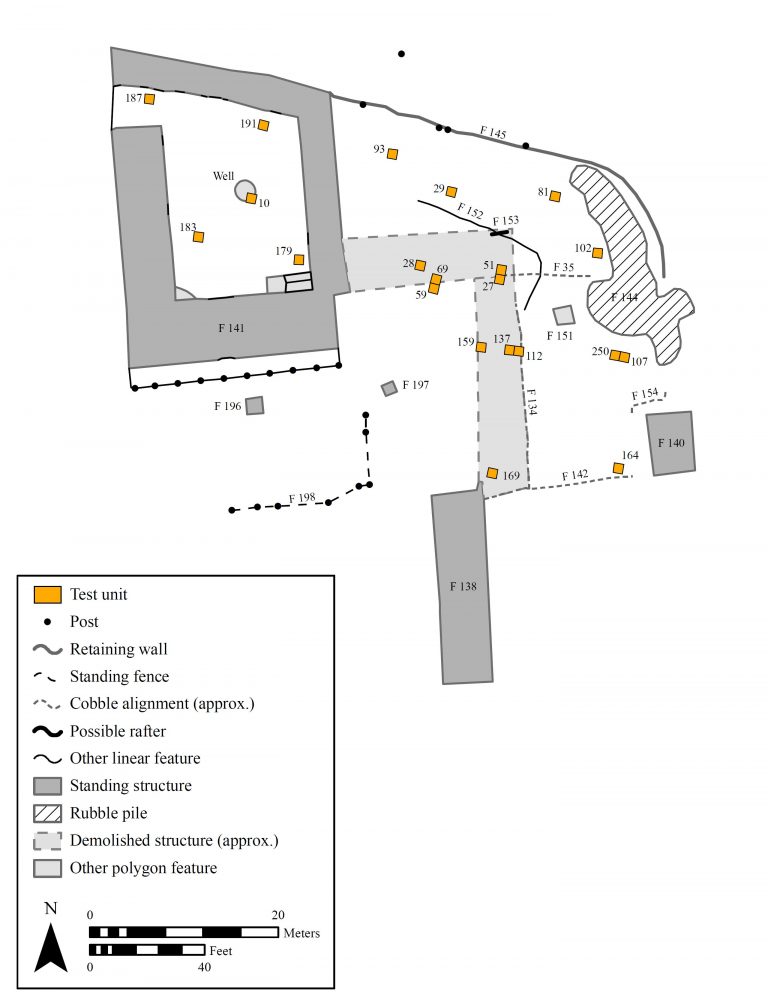

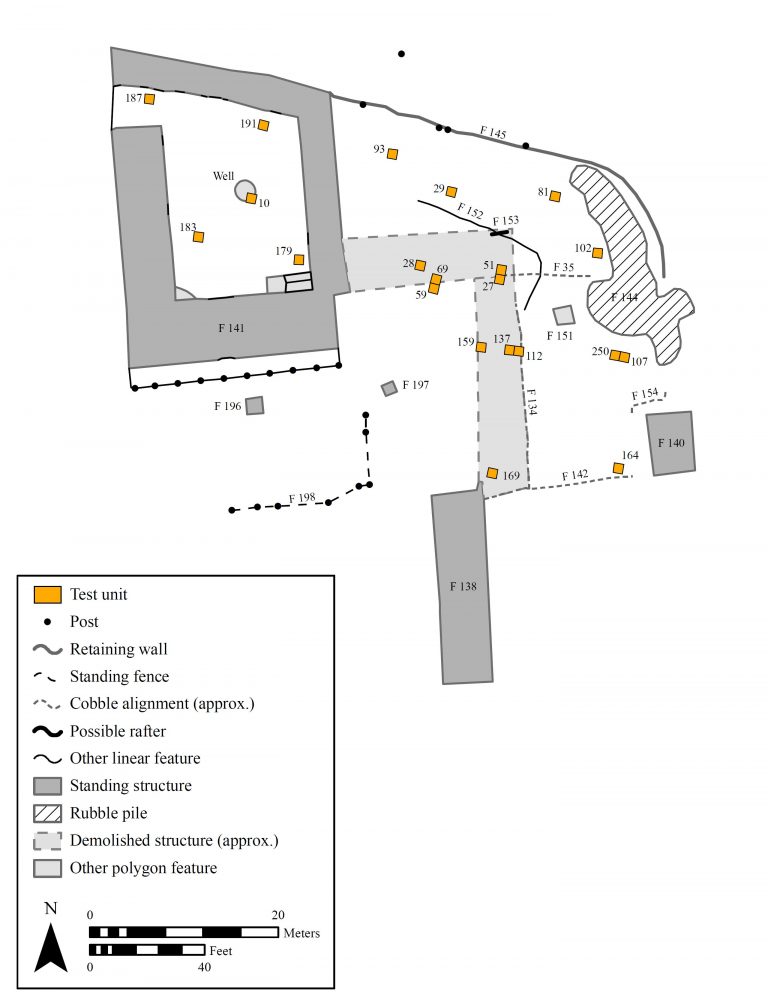

Figure 1. Overview map: northeast corner of the San Miguel del Vado plaza.

|

Each land grant family received a residential lot (solar) in the village and a plot of agricultural land (suerte) along the river, while the remaining pasture and natural resources of the common lands (ejido) were shared by all of the vecinos. In exchange for rights to these lands and resources, the vecinos were responsible for building a fortified village, digging an irrigation ditch (acequia) to deliver water to the fields, and for governing, maintaining, and defending their community. In performing these tasks, the vecinos provided a service to the Crown by helping to settle and control the colonial frontier, providing a buffer of protection for the more valuable settlements and resources in the interior.

The community of San Miguel del Vado held a prominent place on New Mexico’s eastern frontier throughout the following century. San Miguel’s vecinos welcomed trading parties of Comanches and Kiowas from the plains, and served as a common starting point for parties of New Mexican comancheros and cíboleros heading east to trade with the Indians or hunt buffalos. They welcomed the first party of American traders to travel the Santa Fe Trail following Mexican independence in 1821, and served as a significant resting place and part-time home for many involved in this trade. Five years after capturing and imprisoning an invading force from the Republic of Texas in 1841, San Miguel was invaded and claimed by American forces who marched through the plaza on their way to Santa Fe at the beginning of the Mexican-American War.

In the decades that followed, the vecinos at San Miguel continued to shelter travelers and trading parties while resisting American attacks on their religious practices, cultural traditions, and ownership and control of the ejido. Commercial activity in the village began to decline after 1880, when the AT&SF Railroad was constructed several miles to the north. Young men increasingly were drawn out of the village and into wage labor for the railroad, various mining companies, and large agricultural enterprises springing up in Colorado following construction of the railroad. At the same time, their once thriving sheepherding economy began to suffer as a result of competition (both legal and physical) with American cattle barons and settlers over ownership and control of the grant’s common lands.

|

Figure 2. 2010 Project map.

|

A landmark decision by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1897 claimed that the San Miguel del Vado Land Grant ejido was held in trust for the vecinos by the Spanish and, later, Mexican governments, and thus claimed the ejido as federal property. This ruling reduced the grant’s landholdings from over 300,000 acres to just over 5,000 acres of residential and farming land, stripping the vecinos of the pasture, timber, and other resources provided by the ejido. The consequences of this decision, combined with the economic developments and world wars of the early twentieth century, pushed vecinos further into wage labor and contributed to the village’s gradual decline.

San Miguel del Vado provides a unique view of Spanish land grant communities and of what it meant, day in and day out, to be a vecino. From the very beginning, the community was home individuals of varied cultural and ethnic heritage, brought together through the shared rights and obligations of living in a land grant community. Over the following centuries, this community faced the challenges and blessings that stem from existing along a cultural frontier—at varying times fighting, sheltering, and even producing families with the Plains Indians and later American immigrants approaching from the east. It also weathered the challenges of an increasingly global economy, from the inception of the Santa Fe Trail to the later construction of transcontinental railroads and highways, and from the loss of corporate landholdings to the chaos of the Great Depression and two world wars.

Archaeological investigations undertaken by Kelly Jenks in 2010 provide some insights into the daily lives of the vecinos who created and inhabited this village from the late eighteenth century through the present. With the kind permission of Alicia Bustamante, owner of several adjacent residential plots in the northeast corner of San Miguel’s main plaza, Jenks excavated 21 test units in and around buildings located near the riverbank and along the old Santa Fe Trail (Figure 2). The results of these excavations are described in her Ph.D. dissertation, as well as in articles published for general and academic audiences. You can find links to the dissertation and articles in the section below, along with links to other helpful resources and photographs of the projects.

Land Grant Oral History Project

In 2025, with the support of the National Park Service Historic Trails Office, Kelly Jenks and NMSU graduate student Samantha Nava began doing oral history research with heirs of the San Miguel del Bado (Vado) Land Grant. Seven interviews (and one walking tour) were completed during the summer of 2025. Transcripts of these interviews are currently under review by participants, and when complete, copies will be archived at the New Mexico Farm and Ranch Heritage Museum. Nava plans to share the stories from these interviews in a virtual museum exhibit and in her MA thesis, both of which should be finished before the end of 2026. Links to these will be added to the sections below as they become available!

Publications

- Becoming Vecinos: Civic Identities in Late Colonial New Mexico. In New Mexico and the Pimería Alta: The Colonial Period in the American Southwest, edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves, pp. 213–238. University of Colorado Press, Boulder. (2017)

- Building Community: Exploring Civic Identity in Hispanic New Mexico. Journal of Social Archaeology 13(3):371–393. (2013)

- Vecinos en la Frontera: Colonial History and Archaeology at San Miguel del Vado, New Mexico. SMRC Revista 45(166–169):15–25. (2011)

- “ Vecinos en la Frontera: Interaction, Adaptation, and Identity at San Miguel del Vado, New Mexico.” Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Arizona, Tucson. (2011)

Public/Community Presentations

- Stories of Querencia from San Miguel del Bado, by Samantha Nava. Hosted by El Rancho de las Golondrinas as part of their Talk Tuesday series. (2025)

Additional Resources

Photographs of fieldwork and finds

San Miguel del Vado Church

|

Pecos River“vado”

|

Territorial House (east side)

|

Santa Fe Trail (Territorial House on the left)

|

Territorial House (north block, built in the 1820s)

|

Excavation

|

Wall between two structures (Units 27 and 51)

|

Profile of the unit containing the wooden floor

|

Marbles, most found under the floor beams

|

Earthen floor (Units 112 and 137)

|

Scissors recovered on earthen floor

|

Old roasting pit (containing one bison bone!)

|

Various ceramic fragments

|

Part of a small micaceous olla

|

Corn cob scrape marks on micaceous jar fragment

|

Worked pottery sherd (game piece?)

|

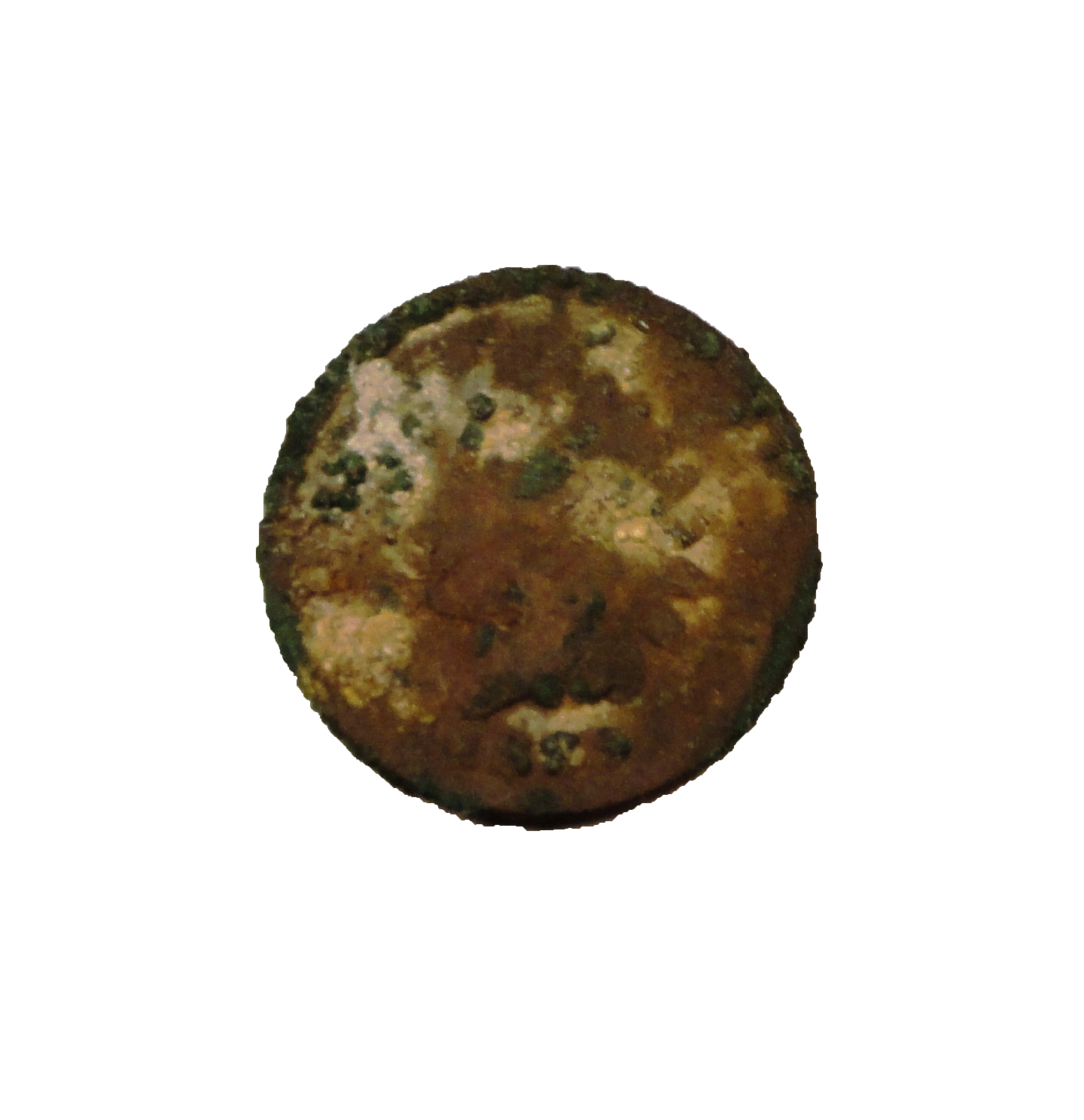

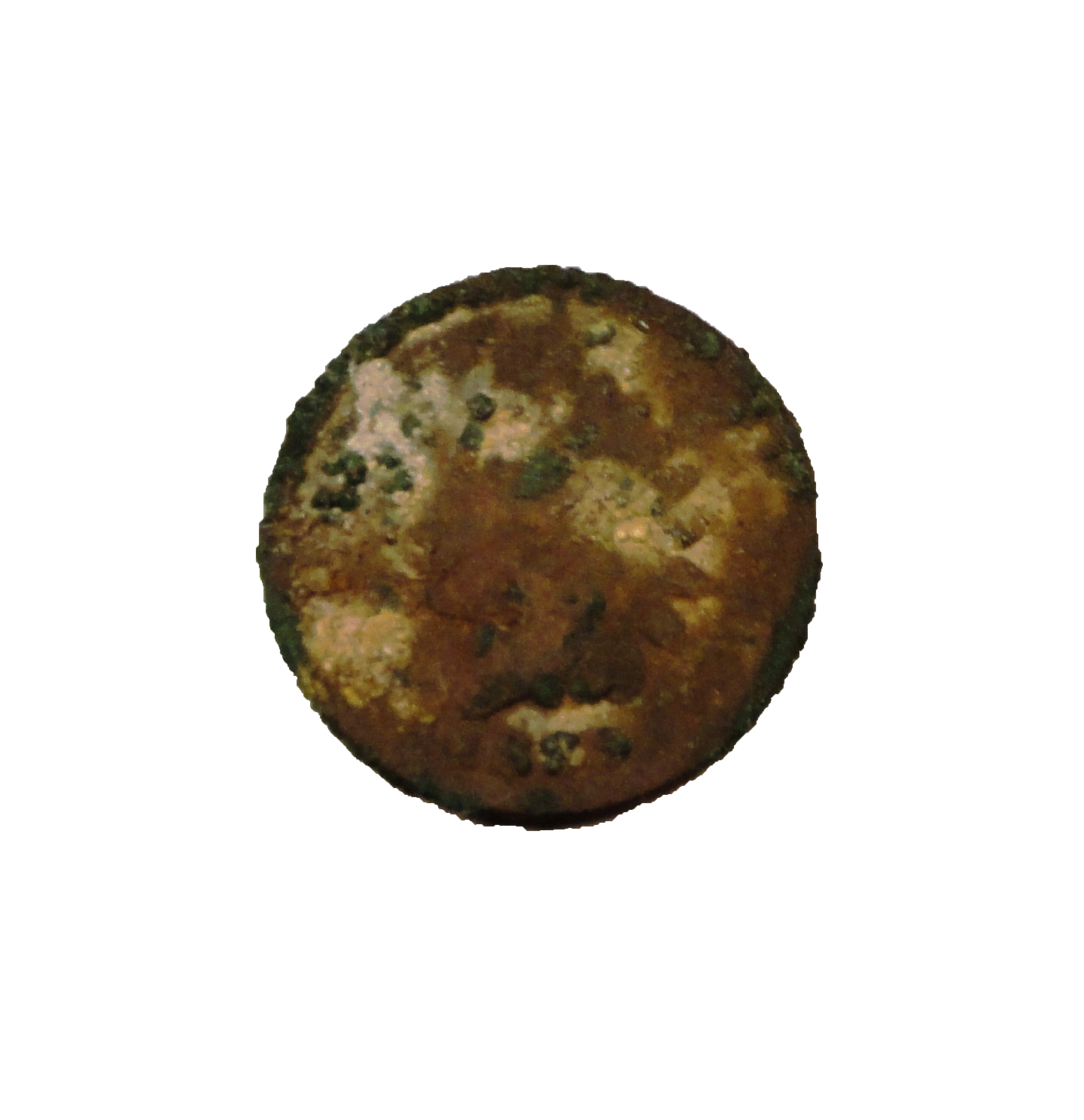

US Army rifleman’s button, produced in Philadelphia between 1807 and 1822

|

“Indian head” cent minted in 1889.

|

“Helping” excavate

|

Heading home–Hwy 3, Pecos River Valley

|